- The Design Manager's Field Guide

- Posts

- We Aren’t Unicorns: Design Skillset Coverage and the Centralized Partnership

We Aren’t Unicorns: Design Skillset Coverage and the Centralized Partnership

Product Design and UX Beyond Agile Structures, Part III

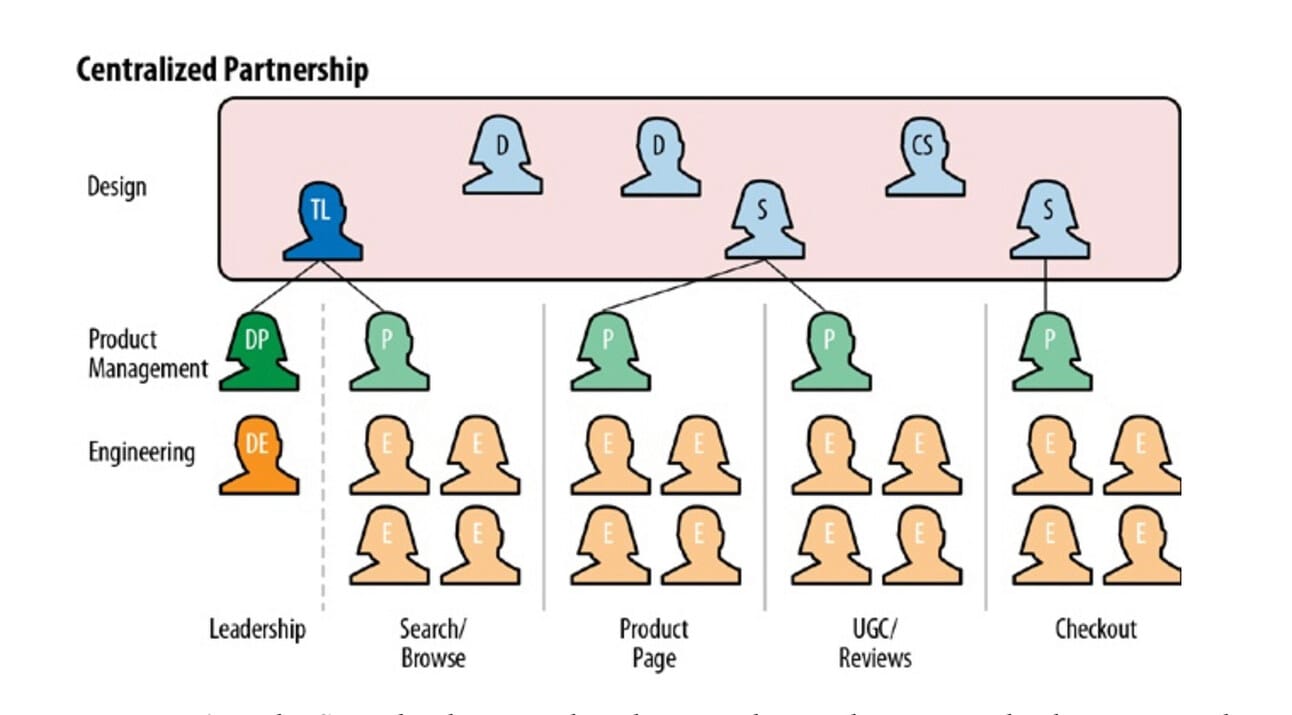

As covered in the first part of this series, the Centralized Partnership model for product design teams is a promising alternative to the more traditional Embedded or fully Centralized models prevalent in many companies today.

Product Design Team Operating Models 101

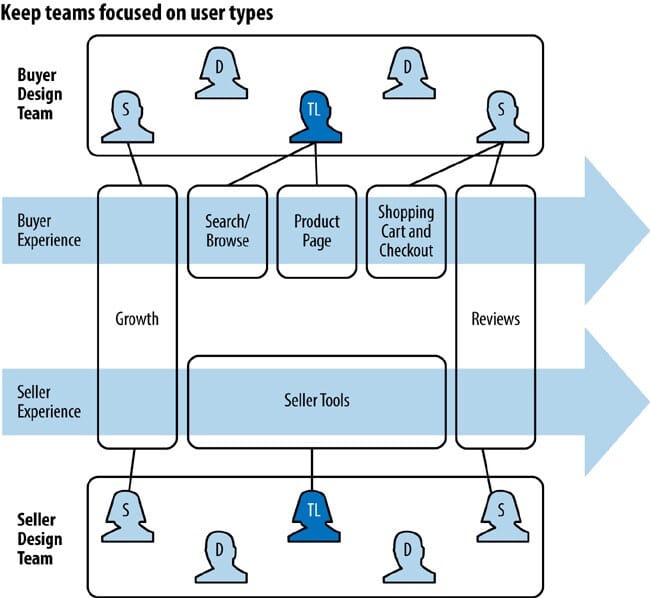

The Centralized Partnership provides the benefits of Embedded and Centralized models while avoiding a number of their limitations. For example, the Centralized Partnership leverages product design teams that are centralized and tied to the user and their journey, resulting in greater design collaboration and a more holistic focus, while maintaining close ties to product teams and business partners through clear lines of responsibility, a benefit of the Embedded approach.

Sound too good to be true? Well, it can be. No single organizational model is perfect, and much of it depends on context, size, and maturity of any given company. In my experience, the downsides of the Centralized Partnership have been minor in comparison to the challenges faced when designers are decentralized and embedded, specifically: siloed experiences, contradictory design patterns, and duplication of effort. Making the switch has so far been worth the effort.

In my last article, Design Leader as Change Agent, I covered the questions design leaders should ask themselves before embarking on the steep mountain climb that is implementing a new organizational model (or any other major change initiative). If you are committed to implementing the Centralized Partnership, the first step is to internalize that unicorns aren’t real despite all the hype, which is especially true in product design.

Do orgs still hire “full-stack” engineers? From a product design perspective, all PDs are “full-stack” and are asked to be experts across all design and user research methods/disciplines. It’s an impossible ask.

— Justin Delabar (@JustinDelabar)

5:07 PM • Feb 23, 2022

Sorry, but unicorns are made up

There seems to be a common belief that a single designer can adequately support all the design and research needs a product may ever have. Or, even worse, the understanding within the organization might be that the designers “feed the developers” with screens, and that is design’s primary or only responsibility. In reality, a designer at any given time might need to be an expert in one to as many as 10, if not more, specializations: generative research, information architecture, evaluative research, interaction design, visual and brand design, facilitation, accessibility, service design, content design/UX writing, strategy… It’s frankly absurd.

Why isn’t the absurdity recognized? In the embedded model, the designer is not surrounded daily by other designers or user research experts. They spend the vast majority of their time with developers, product managers, and business stakeholders who may have a narrow view and understanding of design. As a result, the product team and its stakeholders are likely to accept “good enough” instead of “great,” simply because they lack the context that something better can be achieved through broader design thinking and user research methods. Even when outcomes are good, how much better could they have been if customers were involved earlier, as an example? Early career designers, especially, are put into a tough position in product teams without strong mentorship and coaching. Senior designers can even have difficulty. The recognition of the need for more research, divergent concepting, design thinking, etc. is there — but the senior designer is still only one person. They are not a unicorn or blessed within infinite time, despite the expectation to the contrary.

Quick sidebar: we as designers are not free of blame for the situations we find ourselves in; we change our titles frequently and no one person describes what we do the exact same way. I sometimes get confused. Of course Brenda in Finance has no idea what I’m talking about.

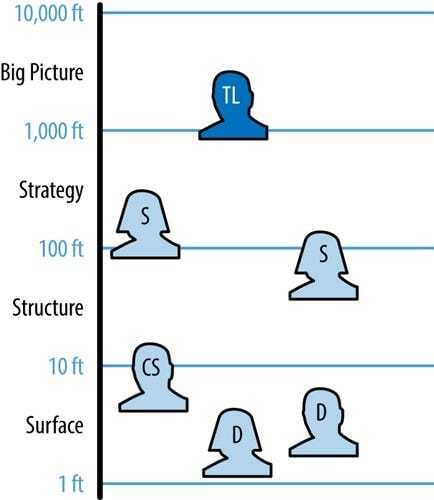

To limit sub-optimal results, design leaders through the Centralized Partnership have the opportunity to assess skills coverage across their teams and make product team coverage decisions accordingly. My intent has always been to staff teams with generalist or T-shaped product designers and specialists that focus deeply on research, UX writing, and UI (design system) design. I also try to have coverage from all levels of expertise, from early career through senior, with the senior designers holding responsibility for higher-level strategy while more junior designers focus on interaction and surface-level details in support of the seniors.

Senior designers may also “own” a product team relationship (sometimes more than one) and confer with one another and their manager to align skills appropriately to meet needs across the product areas that are supported. Peter Merholz covers this staffing approach in detail in Org Design for Design Orgs:

Assessing Skills and Building the Team

In order to create balanced product design teams, step one is ensuring that you and your leaders understand each designer’s strengths and weaknesses. You may already know, in which case: Great! Your professional development approach is working. If you don’t have a good or good enough understanding of skillset coverage across your team, I recommend pulling together a skillset self-evaluation survey.

Step 1: Create a list of skills you believe are critical for your design team to have, including definitions.

Step 2: Build a survey that asks each designer to rate their expertise across each skill. I suggest using a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with a clear definition of what a 5 means (to me it means the designer can teach the skill at the graduate level). You can also include a question asking which skills the designer wishes to improve, which will inform future stretch opportunities.

Step 3: Meet with each designer to review and adjust their inputs. The three times I’ve done this I’ve found that many of my designers actually rated themselves lower on skills where they were uncommonly gifted. Of course, there were others who went straight 5s that needed to be adjusted downwards. Your mileage will vary. Regardless, the conversations served as a great springboard for career development discussion while also giving the context needed to make smart staffing decisions.

With skillset conversations done, I create radar charts for each individual that become part of their individualized career path plans (more on these in a future article). When designers are pulled together into a team, each radar chart can be combined as an average that provides an overview of the strengths and gaps the team has:

When the skills survey is first introduced you may have some designers concerned about how it will affect their performance review or status on the team. It’s important to frame the exercise as disconnected from the performance review process and as an input into career path planning only, including the identification of opportunities that will support future growth. I’ve found the ensuing conversations to be some of the most productive and fulfilling I’ve had as a design leader and coach.

Now with a common understanding of each designer’s strengths and weakness, you are enabled to stack your Centralized Partnership teams with an optimized mix of talent for maximum effectiveness.

Next time in the fourth and final chapter of the Product Design and UX Beyond Agile Structures series: visibility and operations in a Centralized Partnership.

Product Design and UX Beyond Agile Structures Series

We Aren’t Unicorns: Design Skillset Coverage and the Centralized Partnership

Getting Aligned: The Contracts of the Centralized Partnership