- The Design Manager's Field Guide

- Posts

- Right-sizing Design Efforts in Agile

Right-sizing Design Efforts in Agile

Really, you think doing all this in two weeks will work?

I've been vocal about shortcomings in agile frameworks throughout my career, mainly Scrum. My primary criticism is that Scrum emphasizes the delivery of code over value-based outcomes. The delivery emphasis is codified in the Scrum Alliance's key principles:

Working software is the primary measure of progress.

My second gripe is with the fourth principle:

Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

There are two types of people missing from this statement: customers and designers. If you read through the 12 principles, you will notice the words "customer" and "design" appear twice each, although it's unclear what design means in context; it could be back-end architecture design. When the Agile Manifesto was written in 2001 by disgruntled developers, designers were not considered, nor were their methods. That being the case, it should be unsurprising then that Scrum focuses on software development and delivery as the primary means to generate customer feedback and continuous value.

While Scrum's lack of design consideration has led to many disgruntled designers, myself included, no "Product Design Manifesto" exists to disrupt our collective ways of working. Instead, there have been attempts to better integrate design and research methods into Scrum processes, including what I believe to be the most successful: Dual Track Agile. But, before jumping into a new agile process directly, the first step is making sure that you, as a design leader, have your own house in order.

Aligning on design process

In Scrum, designers are likely embedded in product teams, separate from one another. Establishing and maintaining a consistent design process can be challenging since Scrum principles supersede in such an environment. The design leader's goal should be the clear establishment of an easy-to-follow design process framework that plays well within the constraints of the Scrum framework.

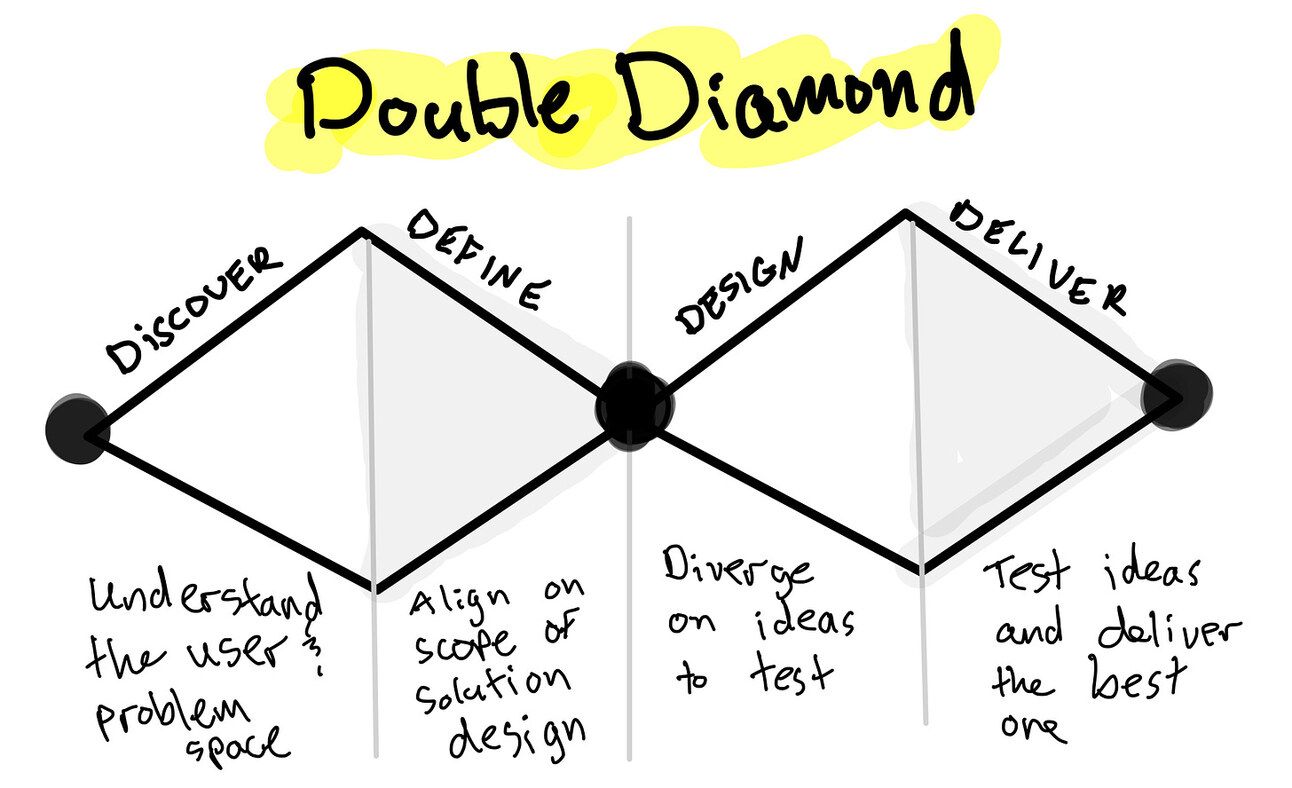

There are many design frameworks from which to choose. Most follow a similar phased structure: understand or empathize with the customer, understand the problem and opportunity, experiment with many options, then deliver the most promising solution. In my opinion, the Double Diamond framework, first introduced by the British Design Council in 2005, is the most straightforward visualization of an end-to-end design process.

I've always grounded my teams in the Double Diamond model. By choosing one process framework to rally around, designers can use shared vocabulary to describe the maturity of their work and bring the concepts back to their assigned product teams. But aligning on the shared process is just the first step -- getting it to integrate with Scrum requires some further thought and modification.

Design and research in Dual Track Agile

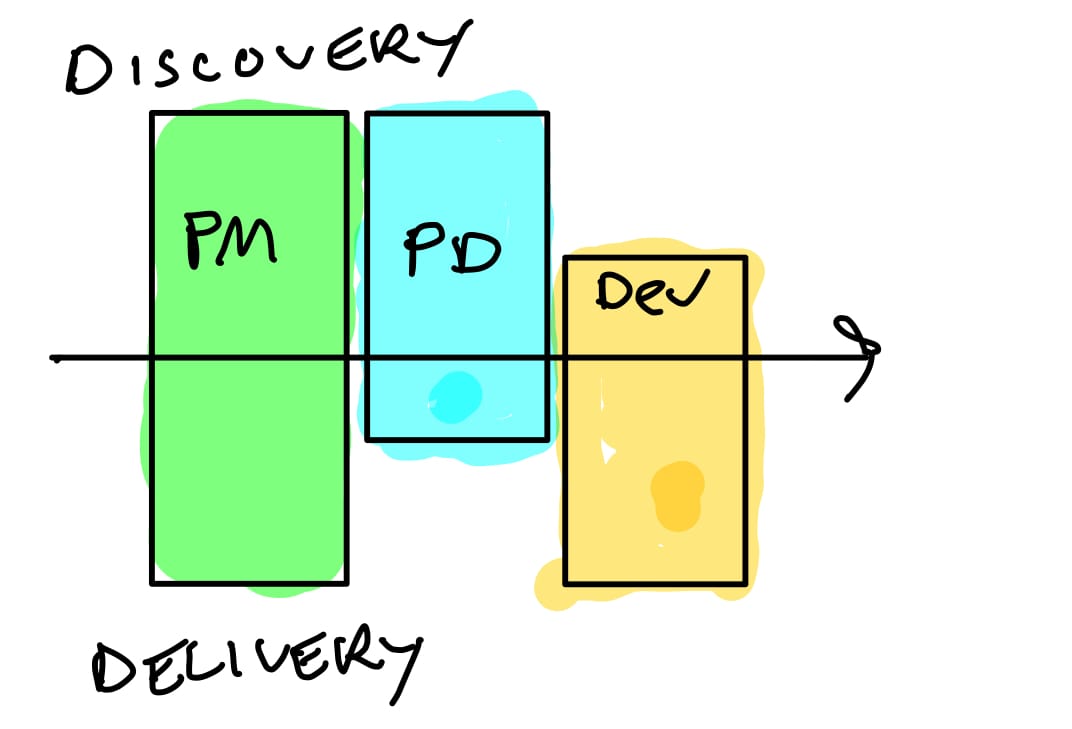

For design to be most effective, it often needs more than the standard two week sprint timebox to run through the Double Diamond process. Dual Track Agile offers a solution through two separate, parallel tracks of work: Discovery and Delivery. The Delivery track is the standard agile two-week software delivery cadence. At the same time, Discovery is slightly out-in-front of Delivery "de-risking" the work to come in the following sprint or sprints. Product Designers spend most of their time in the Discovery track, while Product Managers split time across both, and Developers spend their time mostly in Delivery. All three roles collaborate across both tracks so there are no surprises and each track can inform the work of the other.

Sizing Discovery

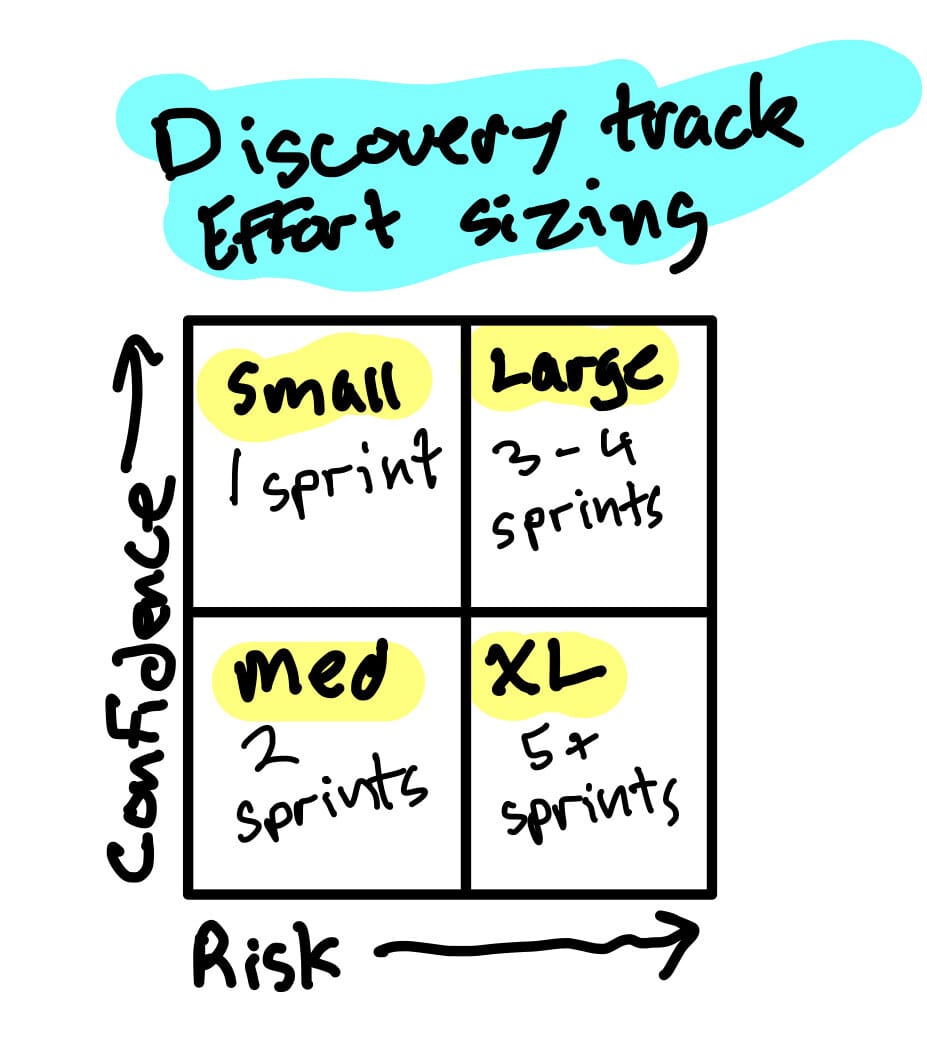

Typically, the Discovery track might operate one to two sprints ahead of Delivery. But, what if two sprints isn't enough time to meet the complexities of the problem faced? That's where Discovery sizing comes into play, an approach I started using back in 2018.

Discovery sizing is a simple process. For a given problem or opportunity, the team should ask itself these two questions:

How confident are we that we would get the design right if we started today?

How high is the risk if we get it wrong?

Confidence is informed by how much the team already knows about the problem through existing research or other data. If much is known -- High Confidence -- hypotheses can be formed to drive design. If there is Low Confidence, more research is needed to increase knowledge and confidence.

Risk is the perceived downside of getting the design wrong, both for the customer and the business. For example, there is High Risk if a payments screen modification could make it more difficult to check out. If the change is to a low-traffic area of the experience that won't directly affect revenue or other core metric, it can be considered Low Risk.

The combination of Confidence and Risk drives the timeline for Discovery efforts. Low Confidence, High Risk initiatives require significantly more time across the Double Diamond process than a High Confidence, Low Risk one. In fact, for the latter the team might opt to skip straight to the Design and Delivery phases of the process.

It's possible to assign Discovery effort timeboxes based on the Confidence and Risk measures. Below you will find the matrix I have used with some of my teams:

The benefits of clear timeboxes based on the size of Discovery efforts is helpful in two ways:

It sets a standard expectation amongst designers and their teams.

It allows the design leader to better understand their designer's focus over time. When combined with all designers on the team, a clear picture of the team's ongoing capacity emerges.

I have found the abovementioned approaches effective, but I'd love to hear from you. What other processes have you tried with your teams? If you've given Dual Track a spin, what are some of the challenges you've faced? Do you have another design process that you prefer over Double Diamond? Leave a comment below or tweet them my way.