- The Design Manager's Field Guide

- Posts

- Are you Designing an Evolution or a Revolution?

Are you Designing an Evolution or a Revolution?

It’s not a trick question.

When I ask designers if they’re designing an evolutionary or a revolutionary experience, they tend to think I’m asking if the work is “good” or “great,” which belies a misconception. There is no value judgement to be inferred or a hidden agenda (I used to be a cranky art director, but I was never that bluntly obtuse with my feedback). I simply mean: what mode of product design are you in: evolutionary or revolutionary? The answer is dependent on how mature the product being designed is and the overarching business and product strategy.

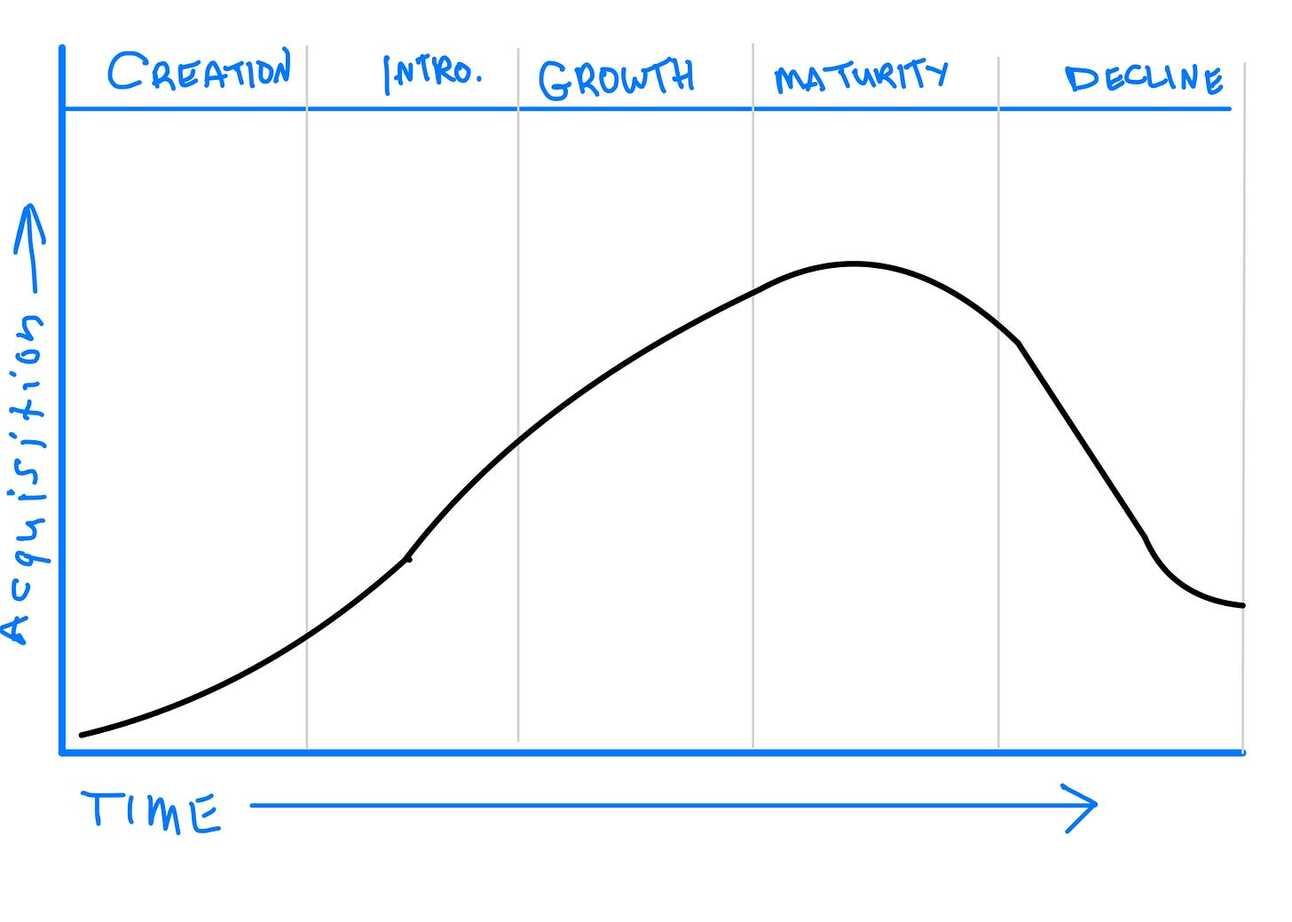

All products have a lifecycle, starting with their creation and launch through their eventual wind-down and sunset. A product at its inception is likely in a revolutionary mode of design simply because there was nothing from which it could evolve. Products in the maturity phase are likely in an evolutionary state — goals have been hit, and the design and product team are seeing how much further they can push the existing experience to achieve more.

This is a bit of an oversimplification, but it illustrates the core point. A product can transition between both evolutionary and revolutionary modes throughout its lifecycle based on the overarching business and product strategy. There are some frameworks that can help determine which mode of design a product should be in, assuming business priority and expectations are set accordingly.

Hope you like data

There’s a big difference between being data-driven and data-informed. I highly suggest being the latter; data points to smoke in the experience but rarely the fire causing user frustration (that’s where research comes in!). I mention this up top because we’re about to go deep into data and metrics, which are foundational to the concept of evolutionary and revolutionary approaches to product design and development.

North Star metric

If you only measured one metric for the product you support, what would it be? What is the one number that when it goes up, you feel great about the existing product experience, but when it goes down alarm bells ring in your head? Your answer is the North Star metric for your product. Ideally the North Star metric is aligned on before design begins, although one can always be set later in the product lifecycle. When running collaborative sessions with product managers, software engineers, and stakeholders, I often find many in the room already have similar ideas of what the North Star should be. When alignment is not so easy, there are methods to get there. But that’s a topic for a future article.

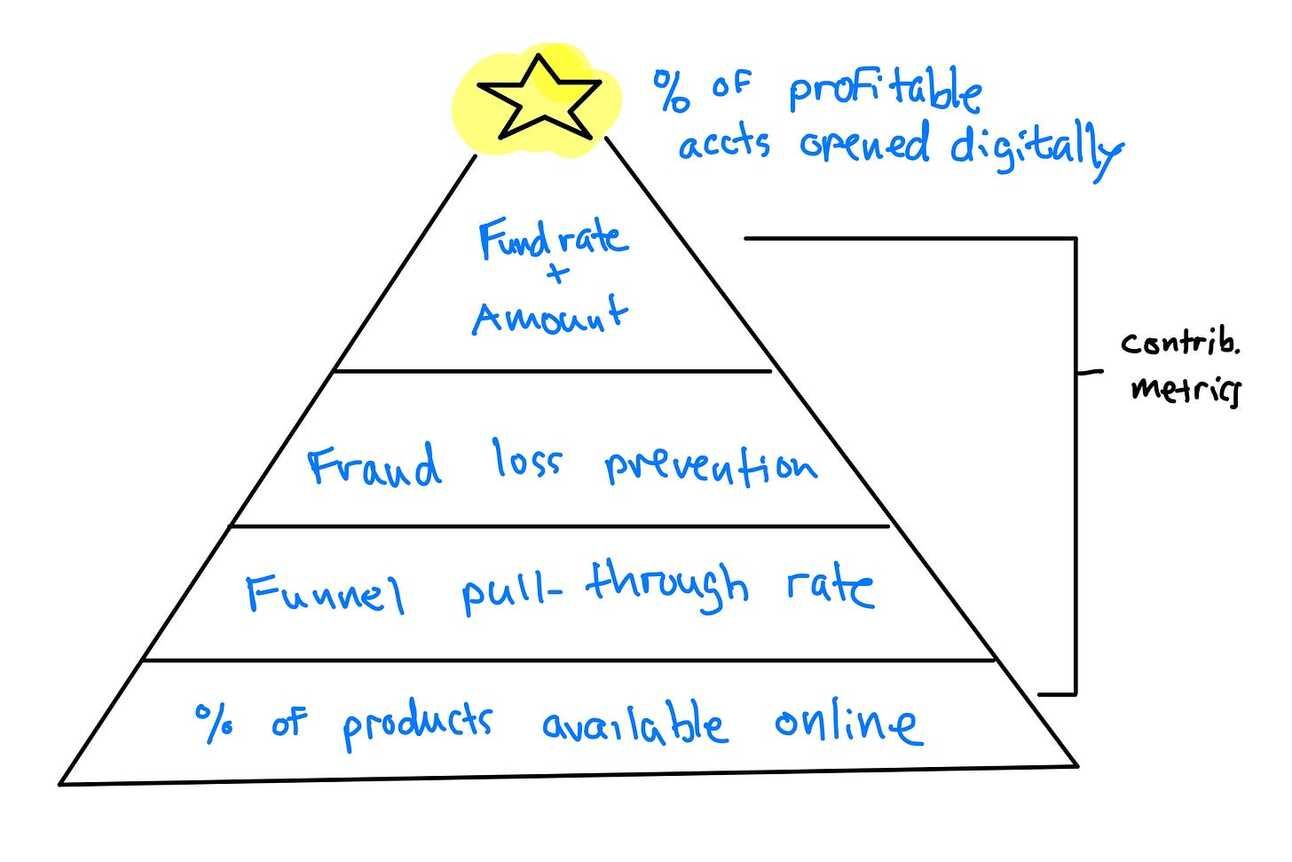

Once there’s alignment on a North Star metric, it’s time to break it apart into contributing metrics. What other measurable aspects of the experience exist that directly impact the North Star metric? Once those are identified, the designer and product team can see “experience levers” they can push or pull to affect the North Star metric.

Let’s take a look at an example from financial services, a common and critical part of a product’s user journey: account opening, with a North Star of percentage of profitable digital account opens in relation to branch opens:

In this example, the product team has a mature product and are looking to improve over previous measures. This is evolutionary design. Now, remember: data-informed, not data-driven. In this process we see the outcome of user behaviors, but we don’t see the whys behind those behaviors. Usability testing, contextual inquiry, think-aloud studies, or other evaluative methods should be implemented to identify what parts of the experience need to be improved, or evolved. Once iterations are launched, the North Star and contributing metrics refresh letting the team know if their changes were successful. And the cycle continues. At least, until the value of iteration plateaus, at which point a strategic product decision needs to be made: move the product toward sunset, or shift to a revolutionary mode of design.

You say you want a revolution?

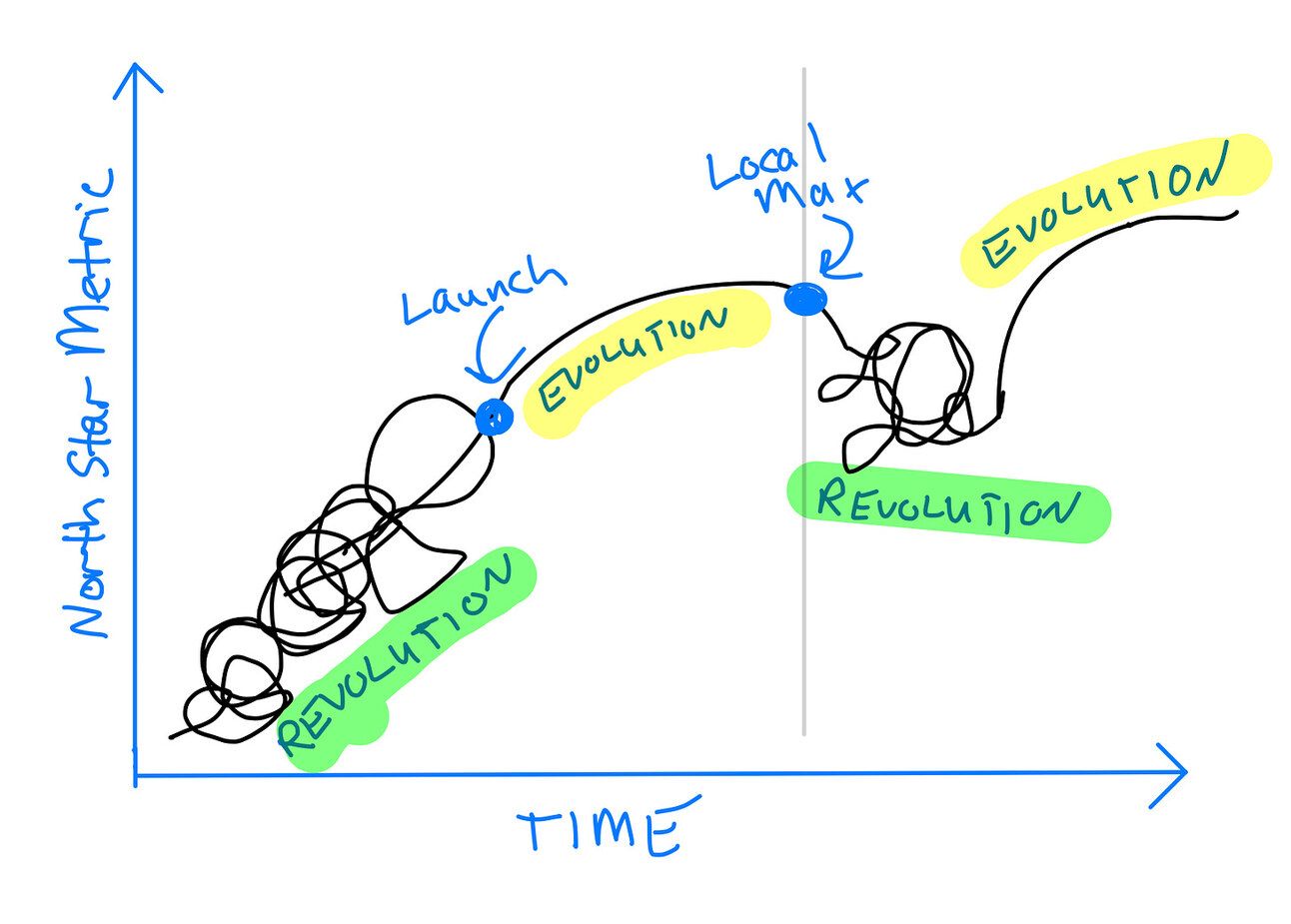

You know what would make this design article better than all this data talk? How about calculus. I get it, I too went into design to never consider complex maths, but the concept of the local maximum in product design is actually pretty straightforward:

Local maximum - When changes to a design no longer yield meaningful improvement, effort to continue costs more than the value returned.

Continuing to iterate on a design that has hit its local maximum is akin to squeezing a rock to get water: you’re just wasting your time and energy. What if the local maximum is hit early on in the product’s lifecycle and outcomes must improve? Time to start a revolution.

The revolutionary mode of design is inherently messy. It’s the first mode a product enters when ideas are raw and many and the sky’s the limit. When a product returns to it, it means what was once revolutionary is no longer enough to push through to the next level target, be it customer acquisition, revenue, engagement, or other North Star metric. At this point, everything in the design is up for reconsideration. New research is run, divergent concepts become many, and, eventually, a new concept emerges to be built and launched. Once in market, the revolutionary design immediately becomes evolutionary — sense and respond to the signals in the data, repeat. Hopefully its first measures clock in above baseline.

Mixed modes

Depending on the size of the product you support, you may find yourself supporting mixed design modes. When broken down into its constituent experiences, some aspect of the product might need to be in revolution mode while others are firmly in evolution. For example, in an e-commerce shopping experience a product display card could be in evolutionary mode while part of the checkout is in revolution due to a plateau, or decline, in funnel pull-through rate.

Should we really redesign that?

Often times designers get asked to redesign a component, a screen, or an entire product— and they get excited, and rightfully so! (No one likes that weird teal you chose, Francis — it’s going bye-bye.) As a design leader, it’s up to you to think through whether or not the widget actually needs to be blown up, or simply tweaked to lead to a better outcome. Utilizing the North Star metric framework and the concept of design local maximums can lead to better experience strategy decisions and more effective, efficient use of designer time.

If you have questions, feedback, or just want to share your story, I’d love to hear from you. You can reach me on Twitter @justindelabar or leave a comment below.